|

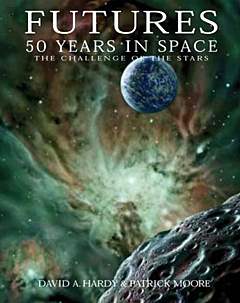

Futures: 50 Years in Space

The Challenge of the Stars

extracts from the book

by David A Hardy and Patrick

Moore

"Dedicated to the crew of the Space Shuttle

Columbia, who died during re-entry on 1 February, 2003. They

accepted the challenge and the risks, but their wish was for their

dreams, and ours, to become reality."

David Hardy's space art

is unique. He creates his own special kind of virtual reality; through

his astounding vision and technique we glimpse landscapes in worlds

where man has never set foot. One of my most treasured possessions

is a painting by David Hardy of a total eclipse in Chile which we

attended together. It captures the awesome beauty of the occasion

far better than any photograph I have seen. So it is in these pages,

where, through David's visionary art, we clearly 'see' the beginnings

of the fulfilment of man's dreams of space.

Futures is a fitting testament to

David's long-standing collaboration with Sir Patrick Moore, who, through

his record-breaking "The Sky at Night" BBC series, has inspired generations

of astronomers. In the pages of this wonderful book these two men

take us out to the stars...and beyond.

...Dr Brian May, Queen

guitarist and astronomer

Pages 6-7

OVERVIEW; 1954-2004

The twentieth century was the Age of  Challenge.

In 1903 came the first manned flight in a heavier-than-air machine;

in 1926 came the first liquid-fuelled rocket; there followed the first

flights above the main atmosphere of the Earth, and then, in 1961, the

pioneer flight of the first spaceman, Yuri Gagarin. By 2000, men had

reached the Moon and unmanned spacecraft had surveyed all the planets

apart from remote Pluto. All this was a prelude to what may well be

the Age of Achievement -- the twenty-first century. Challenge.

In 1903 came the first manned flight in a heavier-than-air machine;

in 1926 came the first liquid-fuelled rocket; there followed the first

flights above the main atmosphere of the Earth, and then, in 1961, the

pioneer flight of the first spaceman, Yuri Gagarin. By 2000, men had

reached the Moon and unmanned spacecraft had surveyed all the planets

apart from remote Pluto. All this was a prelude to what may well be

the Age of Achievement -- the twenty-first century.

When we -- Patrick Moore and David A. Hardy -- first discussed the

idea of a book to be called The Challenge of the Stars, as long

ago as 1954, we hoped that we could make forecasts with reasonable accuracy.

First, an orbiting space-station and then an expedition to the Moon,

establishing a base, small at first but growing steadily. Building upon

the lunar experience, humankind would send an expedition to Mars, perhaps

setting up a base there too. Jupiter's satellites and the outer Solar

System would be the next targets and perhaps, eventually, the stars.

Our schedule seemed logical enough, and the Moon was indeed reached

in 1969, before most people had expected. But thereafter things did

not go entirely according to our plan. By the time the first edition

of The Challenge of the Stars was published, in 1972, humanity

was about to go to the Moon for the last time it would do so

in the 20th century, in Apollo 17. For motives that were political rather

than scientific, the USA had chosen to visit the Moon first in a single,

expendable vehicle. True, a year later NASA did put Skylab into orbit,

and this was in effect a space-station, but it was not intended to be

permanent, and it was not developed. Russia (then the USSR) followed

with Salyut and Mir, and by the end of the century the International

Space Station (ISS) was under construction, but even now there are no

firm plans or commitments to send people back to the moon or set out

for Mars.

There seems to be a 'window of opportunity' within which humans can

choose whether or not to become a spacefaring race while we still have

the knowledge, the means and the resources to do so. Sadly, this window

seems to be closing at an increasing rate. We hope that in some small

way our book will act as an optimistic reminder of what lies out in

space, waiting for our exploration -- and even exploitation, as in minerals

from the Moon and asteroids, together with the advantages of solar power.

Moreover, if we have the foresight and will to make it happen, it will

amaze, excite, and enrich the lives of the next generations: your children

and your children's children.

Remember the words of that great visionary, Arthur C. Clarke, written

in 1968, when the outlook seemed so promising:

The challenge of the great spaces between the worlds is a stupendous

one, but if we fail to meet it, the story of our race will be drawing

to a close. Humanity will have turned its back upon the still untrodden

heights and will be descending again the long slope that stretches,

across a thousand million years of time, down to the shores of the

primaeval sea.

Having said that, the fifty years between our first

visions and today's reality have seen the most amazing discoveries and

advances in astronomy as well as in space technology. In 1954 photography

had yet to be superseded by electronic devices, and some of the ideas

then current seem very old-fashioned today.  The

brilliant, canal-building Martians of Percival Lowell had been consigned

to the realm of myth, but Mars was still believed to have vast tracts

of vegetation. Venus might have jungles, or oceans of soda-water; Saturn

was the only ringed planet, and we knew nothing about the volcanoes

of Io, the lava-flows on Venus, geysers on Triton or the amazing diversity

of the moons of the outer planets. Neutron stars, quasars, pulsars and

black holes were not only unknown, but mainly unsuspected, while estimates

of the age of the universe as we know it were little more than guesswork. The

brilliant, canal-building Martians of Percival Lowell had been consigned

to the realm of myth, but Mars was still believed to have vast tracts

of vegetation. Venus might have jungles, or oceans of soda-water; Saturn

was the only ringed planet, and we knew nothing about the volcanoes

of Io, the lava-flows on Venus, geysers on Triton or the amazing diversity

of the moons of the outer planets. Neutron stars, quasars, pulsars and

black holes were not only unknown, but mainly unsuspected, while estimates

of the age of the universe as we know it were little more than guesswork.

Thanks to the probes such as the Mariners, the Veneras,

the Vikings and the Voyagers, we have learned a great deal since then,

and the developments in instrumentation have been truly staggering.

In 1954 the world's largest telescope, the 200-inch Hale reflector at

Palomar in California, was in a class of its own. Today it is regarded

as being of no more than medium size, and we have of course the Hubble

Space Telescope (HST), soaring high above the main part of the Earth's

atmosphere.

The second edition of The Challenge of the Stars,

published in 1978, did include many changes; the sky of Mars had become

orange-pink rather than dark blue, and Titan, Saturn's main satellite,

was very different from what we then envisaged. But when we came to

prepare this new version, Futures, we realized that the developments

between 1954 and 1978 were in no way to be compared with those between

1978 and 2004. It seems that almost every week brings its quota of new

discoveries -- and space art, as well as space science, has moved with

the times.

Just as the images from space are now gathered or processed

electronically or digitally, many of the new illustrations for this

book were produced on an AppleMac. (This does not mean, though, that

they are 'computer-generated', Although this method of working has undoubtedly

speeded up the process of illustration, pushing paint around on art

board or canvas has mainly been replaced by pushing pixels around on

a monitor!)

Pages 20-21

MARS IN THE 1970s

The problem for telescopes of the 1950s was that Mars never

comes much within 35 million miles of us, and they could never show

it more clearly than a view of the Moon with good binoculars. The first

successful Mars probe, Mariner 4, did not fly past the planet until

1965. One feature it recorded is visible with Earth-based telescopes

as a tiny speck, and was named Nix Olympica, the 'Olympic Snow'; it

was assumed to be a large crater. Only when Mars could be seen from

much closer range was it found that the feature is in fact a giant volcano,

three times the height of Everest. It is now known as Olympus Mons --

Mount Olympus -- and is believed to be the highest and most massive

volcano anywhere in the Solar System. Whether it is extinct, dormant

or even mildly active is a matter for debate.

All our ideas about Mars had to be drastically revised in 1971, the

year we had our first views of the huge volcanoes and the systems of

canyons. Then came the two Vikings, which were launched in August 1975

and reached Mars in mid-1976. One of their main tasks was to search

for life, and this involved making controlled landings; the Lander was

separated from the Orbiter and brought down to the surface, slowed down

partly by rocket braking and partly by parachute. Tenuous though it

is, with a ground pressure below 10 millibars everywhere, the Martian

atmosphere is substantial enough to make parachutes useful.

Both landings were successful. Viking 1 came down in the 'Golden Plain'

of Chryse, 20 degrees north of the equator (10th June) and Viking 2

landed in the more northerly plain of Utopia (7th August). Excellent

images were sent back, relayed by the Orbiter. Rocks were everywhere;

the sky was yellowish-pink, rather than dark blue as had been expected,

and windspeeds were gentle. Temperatures were of course very low --

far below freezing point. One NASA investigator, Garry Hunt, produced

a wry weather forecast for Mars: "Fine and sunny; very cold; winds light

and variable; further outlook similar." Not surprisingly, he proved

to be completely accurate! Dust storms do occur, and can be global,

but in general the atmosphere is very clear.

Each Lander was equipped with a 'grab' -- basically a scoop with a

movable lid, which could collect surface material and draw it back into

the main spacecraft, where it could be analyzed in what was to all intents

and purposes a tiny but highly efficient laboratory. There were three

experiments, all designed to detect biological activity. The results

were decidedly puzzling, but in the end they were generally regarded

as negative, and there was no firm evidence of life of any kind.

Throughout the twentieth century all the useful results from Mars missions

have come from American spacecraft. The Soviet Union launched its first

Mars probe as early as 1961, and others followed. But even today the

Russians have had no success; all their Mars spacecraft have failed

for one reason or another. This is all the more surprising in view of

their excellent results from Venus, which logically would be expected

to pose far more difficult problems.

Obviously, manned flight to Mars must be many orders of magnitude more

hazardous than a trip to the Moon. The astronauts must endure months

of weightlessness and there is, perhaps above all, the danger from radiation;

to provide adequate protection on a spacecraft is very difficult indeed.

Neither are we yet sure whether the thin Martian atmosphere will be

of any real use as a radiation screen.

Yet the Viking results were encouraging enough for NASA to press ahead

with a design for the first Martian base. It would be primitive, but

it would be essential, because the astronauts would have to spend some

months on Mars before it and Earth were suitably placed for the return

journey. Walking about in the open with no protection apart from warm

clothing and an oxygen-cylinder, as envisaged only a few decades earlier,

was known to be out of the question because of the unexpectedly low

atmospheric pressure. Blood would boil inside the body, causing a quick

but unpleasant death. Full pressure-suits must be worn all the time,

and, naturally, any base must be very effectively airtight and pressurized.

In the 1970s it was still thought that the polar caps were very thin,

possibly no more than a surface layer of solid carbon dioxide; only

much later was it found that the caps are thick, and made up of water

ice. We are also sure that even away from the poles there is a great

deal of underground ice, so that future colonists will never be short

of water. In this respect Mars is much more co-operative than the Moon.

In 1972 it was thought that the first manned expeditions might set

off before the end of the century. This has not happened, but it will

indeed be strange if attempts are not made during the next few tens

of years, and will lead on eventually to permanent bases. It is very

likely that 'the first man on Mars' has already been born!

Text and images © David A Hardy and Patrick Moore 2004.

Futures: 50 Years in Space is published by AAPPL (Artists' and

Photographers' Press Ltd, May 2004, ISBN: 1904332137).

Order online using these

links and infinity plus will benefit:

...Futures: 50 Years in Space, from Amazon.com

or Amazon.co.uk.

Elsewhere in infinity plus:

- fiction - Aurora,

an extract from David A Hardy's novel.

Elsewhere on the web:

|

|